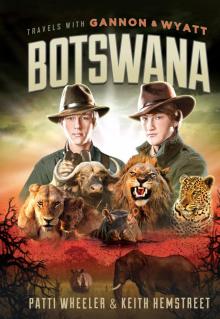

- Home

- Keith Hemstreet

Botswana Page 4

Botswana Read online

Page 4

PART II

SEARCH FOR THE LIONESS AND HER CUBS

Flying over the Okavango Delta

GANNON

AUGUST 23

HIGH ABOVE THE OKAVANGO DELTA

We’ve just passed over the western edge of the delta. The colors of the landscape below us have changed from browns and reds to blues and greens. Such an amazing contrast with the Kalahari being so barren and full of sand and rock and scraggly bushes and the delta being so lush with all kinds of rivers and lakes and giant trees. I’d love to write more, but our plane is getting tossed all over the place by some strong winds, and I’ve already explained how that makes me feel.

Signing off until later …

WYATT

AUGUST 23, 8:23 PM

OKAVANGO DELTA, 19° 07’ S 23° 09’ E

18° CELSIUS, 64° FAHRENHEIT

ELEVATION: 3,021 FEET

SKIES HAZY, WIND CALM

Shinde Camp will be our headquarters while we’re in the delta. A small camp hidden in a forest, Shinde has a dozen or so large tents, including a dining tent and a deck with a fire pit.

We arrived too late in the day to search for the lioness, so we decided to stay overnight at Shinde and go out at first light. Once we have picked up the trail of the lioness, we’ll set up camps in the bush each night until we find her.

As it got dark, we sat around a fire and listened as the nocturnal animals came to life all around us. Singing birds, howling baboons, laughing hippos, and trumpeting elephants were all within earshot of camp. One thing is very clear: We’re on the animals’ turf now.

Chocs explained the differences between the Okavango Delta and the Kalahari.

“In the Okavango, wildlife is much more abundant than it is in the Kalahari,” Chocs said. “Lions, hippos, elephants, leopards, and Cape buffalo can wander through camp at any time. These animals are very active at night. So after dinner you will be escorted to your tent. Once you are inside, do not leave under any circumstances. If you venture out, you will be in danger. You may even hear animals walking past your tent during the night. Just keep quiet. They’ll usually move along.”

“Usually?” I said. “Well, what if they don’t?”

“Don’t worry,” Chocs said with a laugh, “they almost always do.”

Nothing against Chocs, but after the rhino attack, I find it hard to trust him completely. I know he means well and is confident that we aren’t in any danger as long as we do what we’re told, but if the experience in the Kalahari taught us anything, it’s that your safety is never guaranteed in the African bush.

GANNON

EARLY MORNING, STILL INSIDE THE TENT

Picture this: total darkness! So dark that you can’t even see your hand two inches from your face! My brother and I are on cots inside a small tent. Mosquito nets are draped over the cots to protect us from bugs, and we have a thick down blanket to keep us warm. It’s so quiet I can practically hear my heart beat—thump-thump … thump-thump … thump-thump. The only other sound is the soft buzz of the insects, awake and singing under the delta moonlight.

Then, in the not-so-far-off distance, I hear what sounds like a roar. Of course, this makes my heartbeat quicken and I get even more nervous when I touch the canvas walls of the tent and suddenly realize that they’ll do very little to stop a hungry predator from getting to us.

The darkness becomes too much to handle, so I unclip my flashlight from my backpack and shine it in Wyatt’s face.

“Wyatt,” I whisper, “you awake?”

“Yes,” he says, without opening his eyes.

“Did you hear that?”

“I did.”

“What was it?”

“I don’t know.”

“Do you think it was a lion?”

“Probably.”

“What do you mean, probably? What other animals roar like that?”

“None that I know of.”

“So you think it was definitely a lion?”

“Yes. It was a lion, okay. Go to sleep.”

“How am I supposed to sleep when I know there is a lion walking around outside our tent?”

Just then, I hear another roar, and then another.

“Oh, man. There’s more than one lion, and it sounds like they’re coming this way.”

“I bet they’re tracking your scent. Probably think you’re a buffalo.”

“I showered today. You’re the one that stinks.”

“Go to sleep.”

“Are you kidding? I’m not going to sleep a wink.”

“Then why don’t you go out there and shoo them away?”

“Very funny.”

Inside each tent is a blow horn. These horns are left in the tents for emergencies. If you have an emergency you are supposed to blow the horn and at the sound of the horn an armed guard will come running to your rescue … or so we’ve been told.

Assuming that lions entering our tent to tear us limb from limb to limb would be considered an emergency, I take the blow horn off the nightstand. With the horn in hand, I feel more prepared to fend off an attack, but then a thought crosses my mind. What if the horn doesn’t work? What if I press the button and nothing happens? What if there is a manufacturing defect? What if this horn is a stinking dud? I curse myself for not testing it before we all settled into our tents for the night and think long and hard about blowing it for safe measure. “Why not?” I reason. “Better safe than sorry.” Then again, if I blow the horn and the guard jumps out of his bed and comes running through the bush in his underpants only to find that there is not, in fact, an honest-to-goodness emergency, Chocs may begin to doubt that Wyatt and I are worthy of joining him on this expedition.

“Why did I bring these kids with me, anyway?” he might ask himself. “The Okavango Delta is no place for immature boys.”

I don’t want him to have that sort of impression of us. My brother and I have been in many frightening situations before, and given these experiences, I’m pretty sure our courage would measure up to that of the bravest teenager, but this is our first encounter with the king of the beasts, so I’m really nervous and have absolutely no clue what to expect.

Okay, the roars have trailed off, which makes me think the lions are moving away from camp. Maybe they decided to go after an animal with a little more meat on its bones, which is smart on the lions’ part. Together, Wyatt and I would hardly qualify as an appetizer for a hungry lion. Still, just to make myself feel more comfortable, I’m keeping the blow horn close, in my hand actually, with my finger on the button, ready to sound that sucker at a moment’s notice.

A male lion rests before the evening prowl

WYATT

AUGUST 24, 5:53 AM

OKAVANGO DELTA, SHINDE CAMP

5° CELSIUS, 41° FAHRENHEIT

I’m sitting outside our tent, writing in my journal by the flickering light of a kerosene lantern. The sun hasn’t come up yet, and it’s cold. I am wrapped in a wool blanket and drinking hot chocolate that I made on our small camp stove. The benefit of colder weather is that there are fewer bugs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has the Okavango Delta listed as an official malaria area. I am taking malaria medication as a precaution, though I haven’t seen a single mosquito since I got here. I have seen a spider, unfortunately. It was hanging out near my tent. The thing was a beast, too, probably big enough to eat a mouse. With the help of a very long stick, I chased it away.

I can hear some kind of animal moving through the bushes not far from where I sit. It is still too dark to make out what it is, but I do know this: It’s BIG! I’m staying very still in the hopes that I will not attract this animal’s attention.

I slept decently last night, but it sure is eerie to hear so many animals outside your tent. You lie there thinking to yourself, “What in the world is that? It sure sounds like something big, and if it’s big, then that means it’s also dangerous. Darn it, I just remembered that I left a candy bar in my backpack. How could I be s

o stupid? I hope the animal doesn’t smell it and claw its way in for a snack.”

But, despite such nagging fears, we survived the night, and I was able to sleep four or five hours. I don’t think Gannon slept at all.

Today we will set off into the delta in search of the lioness. I have to admit, my nerves are beginning to get the better of me. I hope we get to the lioness in time and don’t run into the poacher along the way. In these situations, it is always the waiting part that kills me. The sooner we leave, the better.

The sun is beginning to illuminate the delta wilderness. I can see just enough to make out the animal in the bushes nearby. It’s a giant bull elephant … and I mean GIANT! His tusks have to weigh 100 pounds each! I’m remaining as still as possible, my only movement being my hand scribbling in my journal. It’s one thing to see an elephant at the zoo, but to see an elephant grazing right next to your tent, that’s a completely different experience altogether.

An elephant eating outside our tent

GANNON

LUNCHTIME

SOMEWHERE ON THE GRASSY PLAINS

A little after the sun came up we piled all of our supplies into the safari jeep and said good-bye to Jubjub and the Shinde staff and set off into the delta. I was really hungry and hoping for a big, hot breakfast, but we were in such a hurry that there wasn’t time for us to sit down to a full meal, so Jubjub packed us each a bag of biscuits and some dried fruits to take along. As Chocs said, “Every minute counts.” It was cold early on but the sun is out and it’s warmed up nicely. We’ve been driving now for a few hours, at least, so we decided to take a short break from the bumpy ride and have a snack.

Out here in the bush there is just nature and nothing else. The feeling of being so far away from everything is really kind of mind-blowing. We’re totally disconnected out here. There are no cell phones. No TVs or computers. I will not be watching the news or writing email or texting or going online. While I’m out here, I will have no idea what is going on in the rest of the world and there is something really nice about that.

At first, being in such a remote place felt kind of strange. I mean, without a cell phone, TV, or computer, it seemed like I’d have nothing to do, so I thought for sure that I’d get bored stiff in no time. I’ve become used to having all these things to occupy my time, but when you think about it, they’re really nothing more than distractions that take you out of the present. What I’m trying to say, I guess, is that these days no one seems to live in the moment. It’s almost like we’re losing sight of things that are right in front of our face.

Our Okavango safari jeep

My brother would probably quote Charles Darwin and say that we have “evolved” and that these distractions have become part of who we are. But out here, the rat race that goes on in other parts of the world is totally insignificant. In lots of ways, life is simplified in the bush. All I really need is something to eat, something to drink, and a place to sleep. And that’s it, which leaves me with lots of time to think and to notice the things that I typically overlook when I’m at home. Out here, you are forced to notice the food you eat, for example, to look at it and really taste it, instead of shoveling it down while you try to do five other things. You are forced to listen to a person speak until they have finished their thought, instead of interrupting them to answer a phone or read a text or check your email. You are forced to live in the moment, because that’s all there is. For me, it’s kind of like my senses have awakened from some long coma and my brain has gotten rid of all the clutter that was bogging it down. Everything seems clear.

Okay, enough with the philosophical mumbo jumbo. Chocs just told us that it’s time to get moving.

On with the adventure …

WYATT

AUGUST 24, 10:47 PM

OKAVANGO DELTA

14° CELSIUS, 58° FAHRENHEIT

SKIES CLEAR, WIND 5-10 MPH

I can’t believe how much wildlife there is in the Okavango Delta! We’ve passed elephants, zebras, wildebeests, giraffes, warthogs, impala, hippos, and Cape buffalos, all by the dozens! Scientists estimate that there are as many as 260,000 large mammals and 500 bird species in the Okavango Delta, and I don’t doubt it for a second. I was so overwhelmed by the incredible number of animals we saw today, I almost forgot about the poor lioness.

But every now and then Chocs would stop the jeep and Tcori would step out and quietly move through the bush to look at something in the grass or pick up something from the ground or check the markings on a tree. Tcori learned to track animals from his grandparents in the Kalahari. Watching him work was a reminder that we aren’t on a typical safari.

Just before sundown, Tcori tore several branches and leaves from a bush and put them in his satchel.

“Inside that bush is a sticky sap that can be smeared on an arrowhead and used as poison,” Chocs explained.

“But why does Tcori need poison?” Gannon asked. “We’re not going to kill any animals, are we?”

“A small dose of the poison will not kill a large animal,” Chocs explained, “but it is powerful enough to knock the animal unconscious. Tcori will use this poison on the lioness so that she will sleep while we remove the bullet.”

I’d never thought about how we would remove the bullet from the lioness, but I suppose she wouldn’t just let us walk right up and start poking around her wound. Keeping her unconscious is not only the safe thing to do, it’s the humane thing to do.

Shortly before dark, we set up an overnight camp—four tents in some flat grass near a narrow waterway. The type of tent we are using has two tarps, each hanging over a wooden frame in the shape of an upside down V. The larger tarp goes on top, providing shade and protecting us from bad weather. The smaller tarp hangs underneath the larger tarp, allowing just enough space for one person to sleep.

After putting up the tents, we had a simple dinner of rice and beans, and a cup of hot tea. There is something about camping that makes any food taste good, no matter how boring the meal. Maybe it has something to do with the process of preparing a meal over a fire while you sit out under the stars. I do love the process and when all was said and done tonight’s simple, yet hot meal sure did taste good.

A family of hippos feeds along the riverbank

After dinner, everyone else settled into their tents. But I stayed up, sitting alone by the campfire, enjoying the incredible night sky. The fact that Chocs had a rifle in his tent lessened my fears somewhat, but to tell the truth, I was still a bit jumpy. When a warthog sprang from the nearby bushes, I was so startled I fell over and scrambled to my tent faster than you can say “goodnight.”

GANNON

AUGUST 25

3:21 AM

For the second straight night, I can’t sleep! I’m inside my tent, tucked comfortably into my sleeping bag and my mind is buzzing with all these crazy thoughts despite trying just about everything I know to slow it down, even counting sheep. Nothing has worked. Every time I close my eyes I see those crazy, black vulture eyes staring at me—all beady and demon-like and just locked on me, almost like they’re marking me for death.

Let me explain.

After lunch we continued driving through delta over the lumpy terrain, bouncing around in our seats as we passed just about every animal imaginable. The sun was out and the wind was a little cool, but just warm enough and I felt really good with almost no fear. I mean, what was there to worry about? We were safe. But sometime later in the afternoon, we stopped so that Tcori could poke around and find some flat, dry land for our camp. He hopped out of the jeep and was strolling around casually, just looking here and there and checking out the location when suddenly he stopped dead in his tracks. I thought he must have seen a pride of lions nearby, but then I noticed there was something above us that had caught his eye. Naturally, I looked up to see what it was. Perched on a high tree branch was a vulture.

I mean, there’s really no nice way to say it, so I’ll just come out and be honest—vultures are hideous crea

tures. And the way it just stared and stared and wouldn’t turn away, jeez, I couldn’t help but think it was a bad sign. A real bad one!

After spotting the vulture, Tcori told Chocs that we had to find another location to camp for the night. Something about that ugly vulture had bothered Tcori, that’s for sure, and if something bothers Tcori, it bothers me.

Before we left, I took out my video camera and filmed the nasty old bird, trying my best to get a nice, steady closeup. I was happy with the footage, but as we drove on, the terrifying gaze of that repulsive scavenger kept appearing in my mind. And here’s the worst part, when I looked up in the sky again, some ways down the line from where we had stopped, there it was, circling high overhead. I couldn’t believe it. Was it actually following us? And if so, why? That’s what I wanted to know. Did it think we were goners? Four more casualties of the African bush? Is that it? Did that ugly bird think we were going to be its next meal?

Oh, man, that thing has got me all freaked out. It’s coming up on 4:00 a.m. now and we have a long day ahead of us and I need rest but I’m still awake and restless and very afraid of what dangers might lie in our path.

Botswana

Botswana