- Home

- Keith Hemstreet

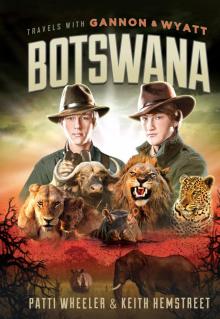

Botswana Page 5

Botswana Read online

Page 5

That old, nasty buzzard

WYATT

AUGUST 25, 9:32 AM

OKAVANGO DELTA, 19° 10’ S 22° 51’ E

16° CELSIUS, 62° FAHRENHEIT

SKIES HAZY, WIND CALM

Early this morning, disaster struck. Not far from camp we drove up to a waterway that was probably 300 feet wide from shore to shore. Chocs said he’d driven through this stretch of water many times in the past and was sure the vehicle would have no problem reaching the other side.

“These safari jeeps are built for this sort of travel,” he said. “The engine is sealed off, and the snorkel extends four feet higher so that the engine can draw enough air to operate even when it’s completely underwater.”

Chocs confidently drove the jeep into the water without a second thought. The first thirty yards or so were smooth going. It reminded me of being in a boat. A low wake trailed behind us. Then the water got deeper, and it began to pour over the side, filling the interior. I lifted my feet onto the seat to keep my shoes from getting drenched. As the water got deeper, the jeep started to look like a submarine trolling on the surface of the ocean. The seats, roll bars, and hood were the only parts of the jeep above the water line. But the engine trudged on.

“When I’m old enough to drive, I want a jeep just like this one,” Gannon said.

“Me too,” I said. “Think of the adventures we could go on in the Rocky Mountains.”

As Gannon and I dreamed of one day having our own safari jeeps, our vehicle was jolted and came to a stop. Chocs jumped up on the seat and looked around.

“Uh-oh,” he said.

“Uh-oh?” I repeated. “That doesn’t sound good.”

“We’ve hit something,” he said.

“A hippo?” Gannon asked.

“If it were a hippo, it would have flipped the jeep by now. It’s probably just a rock.”

Chocs backed up and tried to go around whatever was blocking our path. Again the vehicle came to a sudden stop. The water was crystal clear, so he stood up and looked over the hood, but the underwater algae and grasses made it impossible to see what we’d hit.

“I’m going in for a closer look,” Chocs said and waded into the water. He moved to the front of the vehicle and sank underneath. After a good thirty seconds, he came back up, wiping water from his face.

“There’s a tree trunk under the water,” he said. “It’s too big to go over it, so we’ll have to go downstream and see if we can drive around it.”

But when we backed up, the wheels lost their traction and started to spin. Chocs tried everything he could, but the jeep wasn’t going anywhere. Then to make matters worse, the engine died. Chocs tried several times to restart it, but it was no use.

“Grab your things,” Chocs said. “It looks like we’re going to have to swim for it.”

I had a slight problem with this plan, but it had nothing to do with the swimming part. I can swim. The problem was the giant crocodile sleeping on the shore. Without question, this was the biggest croc I’d ever seen. I kid you not. It had to be fifteen feet long! Chocs said that if we kept quiet and didn’t splash around too much, the croc probably wouldn’t wake up.

“He probably won’t wake up?” I said. “Well for sake of argument, let’s just say that he does? Then what?”

“If the croc wakes up,” Chocs said with a smile, “just swim faster.”

His answer didn’t comfort me in the least. Even if the sleeping croc didn’t wake up, who’s to say that one of his buddies wasn’t hiding just under the water’s surface somewhere nearby? Then again, we were stuck dead smack in the middle of the waterway. What other choice did we have but to swim?

“We’re heading straight for that beach,” Chocs said as he pointed to a beach approximately 150 feet from where we sat in the stalled jeep. “That way, we’ll be swimming with the current.”

We gathered our supplies and loaded them into three waterproof duffels. With our supplies sealed off, we waded into the water. Where we stood, it was nearly chest deep. I began moving quietly through the water in the direction of the slow current, slipping along the muddy bottom toward shore.

I hadn’t been in the water thirty seconds when something slammed into my shoulder. My worst fear was suddenly realized. A croc was attacking!

I screamed for help and spun around to fight for my life. Behind me I saw the long, spiny back of a giant croc floating just above the water’s surface. I swung my fist down on top of it again and again, screaming all the while.

Somehow in the middle of my panic, I remembered having read about a guy who survived an attack by poking the croc in the eyes. As I searched frantically for an eye to gouge, I realized that the creature I was battling wasn’t actually a croc at all. In fact, it wasn’t even a creature. It was, much to my relief, a log. That’s right. A big, slimy log!

My relief quickly turned into humiliation. I felt so foolish for fighting a harmless piece of bark. Even worse, Gannon saw the whole thing. He was laughing so hard he could barely breathe. And I know from past experiences that he’ll never let me hear the end of it. I’m not kidding. We’ll be ninety years old, relaxing on the front porch in our favorite rocking chairs, and he’ll say, “Hey, Wyatt. You remember that time in Botswana when you were so savagely attacked by that log?”

But there was no time to stew over my brother’s amusement. I hadn’t even caught my breath when I heard Chocs yell.

“The croc’s awake! Swim for it, boys!”

I turned just in time to see the giant croc waddling into the water. All of my yelling and splashing woke him up, and he didn’t seem too happy about it. We all swam as fast as we could toward the shore, but the croc was closing in on us fast, its tail slithering like a snake in the calm water. When you’re being chased by a croc, it feels like you’re moving in super slow motion, regardless of how fast you’re actually swimming. Luckily, we were swimming just fast enough. When we finally climbed ashore the croc was still a good fifty feet behind us.

Floating on top of the water, he stared at us as if to say, “You got lucky this time, but I wouldn’t try it again if I were you.”

Don’t worry, Mr. Croc. We won’t.

One of the many giant crocs that calls the Okavango home

GANNON

AUGUST 25

MID-AFTERNOON

Okay, Wyatt’s a pro when it comes to embarrassing himself, but that whole mistaking-a-log-for-a-croc incident might just top every moronic thing he’s ever done in his life. After rolling around on shore laughing until my stomach hurt, it dawned on me: We had a very serious situation on our hands. Our transportation was stuck in the middle of a waterway and there was no way to get it out!

Chocs radioed Jubjub at camp.

“Chocs to Shinde Camp. Come in, Shinde.”

“Jubjub here. How is everything going?”

“Not so good. The jeep is stuck in deep water. We need someone to drive the other jeep to us so we can pull it out.”

“Well,” Jubjub said, “I’m afraid that’s not possible.”

Turns out, the other jeep is out of commission, too. A mechanic is working on the engine, but Jubjub says it needs several new parts that will have to be flown in from Maun. At best, the jeep will be fixed in four days.

I mean, what kind of luck is that? Seriously? I knew that vulture was a bad sign.

“Okay, Jubjub,” Chocs said. “I suppose there’s nothing more you can do. Keep us posted on the progress of the vehicle. I’ll radio you again later.”

“Okay, Dad. Be safe out there.”

“I will. I love you.”

“Love you, too. Over and out.”

Chocs set down the radio and turned to us.

“Gentlemen,” he said very matter-of-factly. “It looks like we’re on our own. From here on out, we’ll travel by foot.”

Fine, whatever, at this stage of the game we really have no choice, but here’s the problem: Being on foot increases the level of danger a thousandfold. Before setting out fro

m Shinde, Chocs told us that when we’re in the truck the animals see the vehicle and all of its passengers as one very large animal—a large animal that they don’t want to mess with—so they are unlikely to attack. Now, this made total sense to me and would have been completely believable, that is, if we hadn’t already had an experience that completely contradicted what he was saying.

“Uh, Chocs,” I said. “What about the rhinos that attacked our jeep?”

“Oh,” Chocs said, almost as if he had already forgotten, “well, that was the exception.”

On foot we’re just four weak little human beings walking around like a bunch of juicy drumsticks. That’s not to say a predator will attack on sight and scarf us down if it happens to be hungry. Even though we don’t match the strength of these predators, they view humans as a threat and usually try their best to avoid confrontation. Again, as Chocs said, there are exceptions to the rule and those exceptions are what worry me.

We’re heading out soon. To prep us for our journey, Chocs just translated some important bush wisdom from Tcori.

“If we encounter a lion,” he said, “do not run. Even if the lion charges, do not run. It is most likely a mock charge, meaning the lion is only trying to size you up and see if you are really a threat. In this case, a lion will halt his charge and turn away. But if you run, the lion will chase you, and if that happens you’re in trouble. What you need to do is keep eye contact with the lion and back away slowly. If you try to hide behind a tree or lie down, a lion might become curious and move in for a closer look, and if that happens you’re in trouble as well.”

“Just to make sure I understand this correctly,” I said, “the idea is to stay out of trouble.”

“Precisely,” Chocs said with a toothy grin.

Okay, just for the record, if we do happen upon a lion and it does decide to charge, I’m not so sure I’ll be able to hold my ground. If I’m not mistaken, there’s something called the “fight or flight” response that is embedded in our brains at birth. If a lion were bearing down on me, I know one thing: My brain would choose “flight.” I mean, isn’t it human nature to run from something that can tear you limb from limb?

Oh, man, I just hope that I’m able to remember this advice and not freak out like Wyatt did when he encountered the tree-stump croc. To improve my chances of reacting like we’re supposed to, I made up a little saying that I’m repeating quietly to myself. It goes like this: “Stay calm, keep eye contact, and back away slowly … Repeat.” My hope is that if I say it enough it will become ingrained in my mind and I’ll be able to overcome the “fight or flight” thing and react appropriately.

All these dangers aside, the aspiring filmmaker in me can’t help but see this adventure as a chance to get some amazing footage. I honestly can’t think of anything more intense than capturing a charging lion on film—his mane drawn back in the wind, a dust cloud swirling behind it, his eyes locked on the camera. That kind of footage would put me in the ranks of some of the great wildlife filmmakers of all time—that is, if I could keep my hands from shaking so bad that people would think I’d filmed an earthquake.

Knowing that Chocs has a rifle and that he and Tcori have a lifetime of experience in the bush makes me feel a little better about our chances of surviving this journey. Both of them know how to navigate the African wilderness, and more importantly, how to behave around animals. Without them, Wyatt and I would definitely slip a few notches on the food chain.

Chocs and Tcori seem to think that abandoning the jeep was probably a blessing in disguise because the lioness was shot by a poacher driving a truck and would probably run at the first sound of an approaching vehicle. According to Tcori, on foot we’ll have a much better chance of finding the lioness and her cubs.

In a few minutes we’ll continue moving south until an hour or so before it gets dark. That’s when we’ll scout out a good location to set up camp and stay the night. Fingers crossed all goes well.

WYATT

AUGUST 25, 11:47 PM

OKAVANGO DELTA

13° CELSIUS, 55° FAHRENHEIT

SKIES CLEAR, WIND CALM

I am awake and, to be completely honest, not feeling as strong as I would like. I think the day’s excitement, combined with the long trek through the bush, has sapped me of all my energy. It is difficult even to write, but I have to make a few notes about our experience with the elephants today.

Walking along a dried-out riverbed, we encountered for the first time the sad consequences of poaching. Under the shade of the trees, we saw a female elephant lying on her side with a severe wound to her right hind leg. She had stepped into a poacher’s trap, and a wire snare was wrapped tightly around the lower part of her leg. The snare had torn through the elephant’s tough skin, and the wound had become terribly infected. The infection was so bad the elephant could no longer walk.

Tcori said there was nothing we could do. This poor elephant was dying, and it was only a matter of time before the scavengers moved in to feast on her remains. Once the scavengers had done their job, the poacher would return to collect the tusks. In an effort to prevent this, Chocs radioed the elephant’s coordinates to Jubjub, who, in turn, radioed the authorities. It is the practice of the government to remove a dead elephant’s tusks and store them in a vault. They do this to keep the tusks out of the poachers’ hands.

A large bull elephant circled the female elephant like a husband mourning his wife. With his tusks, the bull tried desperately to lift his companion. It was as if the bull would not accept the sad fate of his mate. It even appeared that the bull was crying. Chocs explained that elephants have glands located just behind their eyes that excrete a fluid when they get stressed. This fluid, which streams down the side of an elephant’s face, looks like tears.

To me, the tears were proof that the bull elephant was sad. People think animals don’t feel. That’s not true; animals do feel and some, like the elephant, show great emotion.

With that, I must now close this entry. I am feeling weaker and more feverish with each passing minute. I have to get some rest if I hope to feel better by morning.

GANNON

AUGUST 26

2:07 PM

It’s official. There’s no disputing it. Just as I thought, the vulture was a bad omen. Our expedition is cursed!

First, there was the jeep, then we come across the dying elephant—which, for the record, was one of the most awful things I’ve ever witnessed and made me so upset that I can’t even write about it—and now, to top it all off, Wyatt’s sick.

He woke up this morning with a high fever and the chills and he was all pale and looked terrible. Before the trip, my mom told us about the different illnesses people can get in Africa. Of course, we took steps to protect ourselves from lots of them. Like, for example, we’re taking malaria medication, so we highly doubt that Wyatt has malaria. And we were also vaccinated for hepatitis A and B, polio, typhoid, and yellow fever, but there are lots of other illnesses that have no vaccination. Dengue fever, which you can get from mosquitoes, is one example of a nasty illness you really can’t do anything to protect yourself from, well, other than wearing bug repellent, but the thing is, we haven’t seen many mosquitoes since we got here because of the cool temperatures and all. Wyatt does have a few small welts from some kind of bug bite. I remember reading that tsetse flies could be found throughout sub-Saharan Africa and that a bite from one of these bumblebee-sized insects could cause “African sleeping sickness,” which is pretty serious and causes fatigue, aching muscles and joints, and really bad headaches. So I thought maybe that’s what is making him sick, because he has all those symptoms, but Chocs told me that tsetse flies were eradicated from Botswana years ago.

Other than insects, I’m told there are all kinds of bacteria in the delta water that can definitely mess with your system. This bacteria doesn’t bother the natives. They’ve grown up drinking the water, so I guess their digestive systems are used to it, but the bacteria are foreign to us and

can cause all kinds of intestinal problems if swallowed. We’ve been boiling most of our drinking water and that kills the bacteria and other bad stuff and we also have a small supply of iodine tablets to purify the water when we don’t have time to boil it. Wyatt and I haven’t had a drop of untreated water that I know of, unless he swallowed some when we swam ashore. Maybe that’s it, who knows?

With Wyatt being too weak to travel and all, our search for the lioness has been put on hold. Tcori spent a lot of time in the bush today, gathering roots and things that the Bushmen use to treat fever. While he was out he found signs of the lioness and her cubs and thinks that we’ll reach them soon. I know the clock is ticking and I want to get to the lioness right away, but the most important thing is Wyatt’s health.

Right now, Tcori is boiling up the roots to make some kind of concoction for Wyatt. I’ve got my fingers crossed that this Bushmen brew works some real magic. If his condition gets much worse we’ll have to abandon our search completely and if that happens the lioness and her cubs will definitely die and I don’t even want to think about that. Seeing that poor elephant today and with Wyatt sick and all, I’m just in an unhappy sort of mood and the thought of the lions dying makes it even worse.

Another thing that’s bothering me is that I haven’t sent a message to our parents about Wyatt. I actually told Jubjub not to. Not yet, at least. I mean, there’s nothing they can do so I don’t want to worry them if this all turns out to be nothing. There’s not a whole lot we can do, either, and that’s the frustrating part. There are no doctors in the bush, so when you get sick out here, you’re on your own. I have faith in the Bushmen remedies, but if the situation gets bad enough, Jubjub can ask the authorities in Maun to call for an airlift to the capital city of Gaborone, where there is a hospital. I really hope it doesn’t come to this. If it does, it’ll mean Wyatt’s life is in danger.

GANNON

Botswana

Botswana